Secondary trauma can result from living or working with children who have been through traumatic life events. All people who live closely alongside traumatised children and adolescents, including adoptive parents, permanency carers, social workers, and school staff are at risk.

When a person is experiencing secondary, or vicarious, trauma, they can exhibit signs like the traumatised children they work with, without having endured any trauma themselves. Staff may begin to experience their pupils difficult feelings, either about themselves or others. Those experiencing secondary trauma may not be aware at the time of what is happening though them.

When people experience secondary trauma, they might feel or experience:

These thoughts and feelings can feel shameful to both parents and professionals. After all, we are the grown-ups, so surely we are supposed to be able to cope? Negative feelings towards the child may be even harder to face or admit to. Even if we recognise that we are feeling is the effects of the work we are doing, we may judge ourselves as unprofessional for somehow failing to keep our professional hat on.

Blocked care is a related idea to secondary trauma that is increasingly acknowledged in the adoption world. As it is based on sound neuroscience, blocked care may be a helpful idea for staff who balk at more touchy-feely explanations.

Therapists and Psychologists Dan Hughes and Jonathan Baylin (2012) explain that infants have evolved to activate the reward systems in adults brains to motivate adults to look after them. This is very important if the adults are to keep caring for them despite the adverse effects of being a parent, such as very little sleep. Many of us experienced feeling slightly cross towards a baby who wont stop wailing, only to forgive them everything when they catch our eye or smile at us. Hughes and Baylin explain that our dopaminergic, or reward, system is flooded with dopamine in this moment, and that we are hooked, doing everything we can to make the infant happy and elicit another smile or giggle.

Teaching or parenting an adopted or a care experienced child, however is harder. They do not always respond to our care, affection and attention in the ways that typically developing children do. We might work hard to gain a child’s trust, only for them to be suspicious or treat us as their abusers. We might feel we are getting on well with a child only for them to seem to turn on us in hostility. We might offer a lot but feel continually rejected. When this happens, our reward system runs low. The systems in our brain that support empathy start to shut down in an attempt to protect us from rejection and pain. We might feel unmotivated and then feel guilty about feeling unmotivated. Our natural instincts to care for the child are blocked.

Experiencing this block doesn’t mean we are uncaring people. It is crucial staff know this, to understand themselves and their colleagues. It also gives them a framework through which to understand adoptive parents and permanency carers who may be burnt out at times by many years of intensive parenting.

Below is a handout about burnout and secondary trauma and its impact for leadership and staff to keep in mind – Leadership and School Management staff should ensure all of their school based staff have a copy of this to ensure they are aware of the signs of burnout

Take a moment to reflect…..

| Psychological | Physical | Behavioural |

|---|---|---|

| Irritability | Sleep disturbances | Increased risk taking |

| Anxiety | Change in appetite | Over or under eating |

| Depression | Easily startled | Aggression |

| Anger | Stomach problems | Hyper-alertness |

| Mood swings | Headaches | Listlessness |

| Feeling ‘over emotional’ | Rapid heart rate | Often late to work |

| Emotional numbing | Fatigue | Often calling in sick |

| Poor concentration | Muscle tension | Often working overtime |

| Intrusive thoughts | Unable to relax | Change in smoking and drinking behaviours |

| Disorganised and confused thoughts | Back and neck pain | Change in personal grooming and/or hygiene |

| Forgetfulness | General aches and pains | Decline in performance |

| Indecisiveness | Loss of libido | |

| Cynicism | Pacing | |

| Doubt | Nail biting | |

| Alienation | Awkward body language | |

| Loss of hope | ||

| Feelings of emptiness | ||

| Self-blame | ||

| Disillusionment | ||

| Reduced sense of accomplishment or purpose | ||

| Mental Apathy | ||

| Feeling overwhelmed | ||

| Boredom |

Secondary trauma and blocked care are not good for staff, students, or schools. They result in tightly wound environments where everybody feels fraught and staff turnover is high, making it even more difficult for the school to settle.

We cannot ask staff to do the difficult job of looking after our adopted and care experience children and young people unless we look after them too

We encourage your school to include staff in its mission statement, with acknowledgement that staff care ultimately affects student care. Leadership and School Management should set the tone in valuing staff as the school’s most important resource. Make it clear that you respect and encourage a balance of work and personal life, including the risk associated with working with traumatised students. If staff do being to experience an emotional reaction, they will not feel weak, ineffective or powerless, but will be able to seek support without fearing judgement.

Promoting wellbeing through holding wellbeing days in which staff are encouraged to destress and unload can send a strong message that your school cares about its staff.

Peer support can serve as an important coping resource for those working with dysregulated children. Sharing experiences with other educators can allow staff to vent their feelings, normalise their emotional reactions, and decrease feelings of isolation. Team members can act as a source of validation and resilience for their co-workers. They can help each other to see other perspectives when they are caught up in experiencing the child’s behaviour as personal to them. You could set up facilitated groups in which staff can come together to reflect on their practice and debrief after stressful situations. Having a structured discussion that maintains empathy for both colleagues and the child can be helpful to staff.

Teachers do complex work in relation to children’s psychological and safeguarding needs, which can take a heavy toll on them both professionally and personally.

Supervision is not about performance management. It is not about checking, measuring, or evaluating what staff are doing. It provides a safe, supportive, confidential space to process current practice, reflect professionally and personally and develop professional practice. When it works well, supervision can reduce stress-related sickness, improve staff retention, and ensure staff can give their best to children.

Self-care involves looking after ourselves in terms of our lifestyle and work-life balance, both overall and day-to-day. Self-care can be difficult to prioritise for caregivers, including teachers, yet it is essential in preventing burnout and helping staff to maintain empathy for students.

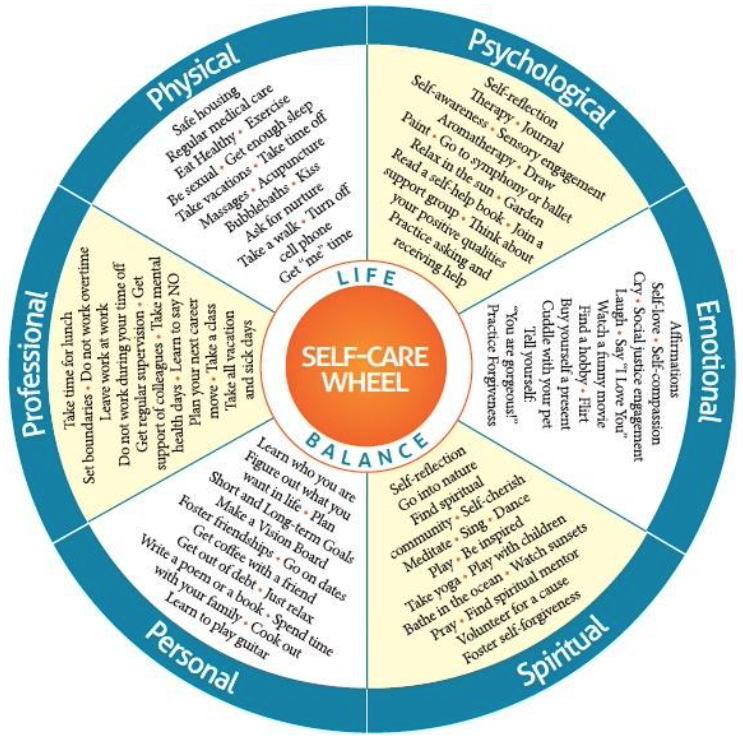

Below is a self-care wheel that sets out some different ways you can apply self-care.

Work together with colleagues to think about how your school supports self-care in each of these six areas. Below is a blank Whole School Self-Care support chart for you to fill in as a group/school team. It is hugely helpful to gain the views of the staff in your school to understand the ways in way they feel supported in each domain. This will show you where your school is doing well, and which areas staff feel they have less support in.

| Area of Self-Care | What we do well | Next Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | ||

| Emotional | ||

| Intellectual | ||

| Social | ||

| Creative | ||

| Spiritual |

The schedule of education is often jam packed down to every last minute and so the first step in maintaining well-being is building in time to look after yourself. This may involve saying no to extra commitments, both in and out of the workplace. A good way to start might be making sure you take your full break/lunch and spend it doing something for you.

Lack of sleep over a prolonged period can have hugely detrimental effects on your health, psychological well-being and performance at work. For improved concentration and mood, research suggests we should be getting between 7 and 9 hours of sleep every night. Try to stick to a sleep routine which allows you to feel fully recharged. A more awake you will make for more awake students and give you the energy to remain strong in the face of adversity

Taking time to talk with co-workers, friends and family can act as catharsis and release built up stress, especially after a bad day. Sharing your experience and feelings with others can also help you gain perspective on tricky situations. But don’t just talk about work – make sure to spend time relaxing and having with others as well.

It’s easy to fall into a pattern of moving between home, car, classroom, car and home again without ever really being outdoors at all during the day. When we are constantly “cooped up” we miss out on the natural world around us. Nature is peaceful and restorative for many people. Incorporate some light exercise into it for an extra boost. A brisk walk around a park can work wonders.

Teachers spend so long trying to develop the knowledge and skills of their students that they can often forget to attend to their own growth and personal development. This looks different for different people and could involve new training, revisiting an old hobby, attending a local crafts workshop, or reading a book. Whatever takes your fancy.

The BRIGHTER FUTURE project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.