There are four forms of communication that almost always go together: verbal communication, nonverbal communication, para-verbal communication, and communication patterns. Para-verbal communication refers to the use of tone, speech rates, pauses or hiccups that allow the message to take on a different meaning. Communication patterns strongly influence the content and level of the relationship of an interaction. An example to illustrate: In some cultures, people generally communicate directly.

That means that when someone says ‘a’, they mean ‘a’. In many non-Western cultures, indirect communication styles are more common. When people in those cultures say ‘a’, they do so with such intonation, pitch, and emphasis or with a certain facial expression (non-verbal) that everyone from that culture understands that what is meant is ‘b’. It is helpful for education professionals to know that there might be different communication patterns than those to which they are accustomed.

Expectations that do not come true and communication problems can lead to mistrust and disappointment on both sides. We now know that accessibility and quality of education can also depend on the ability of professionals and institutions to deal with differences in background, education, gender, migration history, and other relevant distinctions.

This requires knowledge, culturally sensitive skills, and communication. In the case of refugees, it also requires empathy for what it means to have had to leave your country, work, and loved ones. Perhaps to have lived in fear, uncertainty, and war for a long time or endured torture, rape, or violence. Building trust is critical here. One way to do this is to actively invest in getting to know and understand the child and their family. Talking about their background, family, and life in their home country, the experiences that led to migration or flight, and their feelings about this, help to gain trust.

It is stated that the moment a person says something, they simultaneously perceive the nonverbal reaction of the other person in response to what is being said. If the listener raises an eyebrow or gives an affirmative nod, this influences the course of the conversation. Thus, there is a permanent simultaneous interaction. One can assume that we are always communicating. Even failed communication, such as when a misunderstanding occurs, has consequences for the further course of the communication and relationship. Every interaction, whether effective or not, should be seen as communication. Then when a misunderstanding arises, you have to communicate about it; we can eliminate miscommunications precisely by communicating about them.

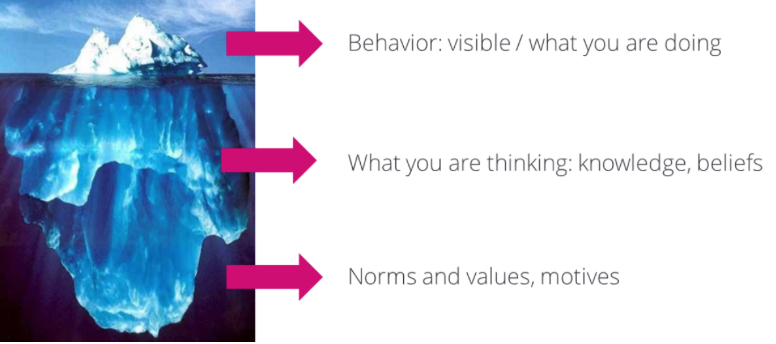

Culture, in particular, seems to be under the surface of the iceberg. The things you can perceive, such as language or (sometimes) appearance, only make up 10% of the culture somewhere or in someone; the famous tip of the iceberg. Most of it is under water and often subconsciously so.

The BRIGHTER FUTURE project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.