We should analyse our students’ lives and our policies and practices with an intersectional approach in mind. This means we consider our students’ multiple identity markers simultaneously, not focus on one at a time, and understand students face discrimination on multiple levels. For example, a student with ADHD may also have another identity marker (e.g., being from a migrant background or having low financial means) that further marginalises them. It is important to note that it is not the category itself that causes marginalisation but rather the societal implications built around it; social stigma is enacted and attached to these categories, and discrimination and exclusion of these students occur as a result. These factors are interconnected. If our approaches to diversity work and interventions do not view them as such and instead focus on one identity marker at a time, they will most likely fail. Teacher education should include notions that all forms of oppression should be addressed; otherwise we also risk creating a hierarchy of needs where some student’s necessities are prioritised over others.

Returning to our hypothetical student: we could enact a program to offer academic support for students with ADHD, including measures aimed at addressing the stigma they face because of the ADHD label. But if we ignore the intracategorical variations, i.e., treat all ADHD students as similar and attempt to give them all the same support, our efforts are bound to fail.

Our hypothetical student, for example, may be further struggling with a language barrier. The support programme meant to help them manage ADHD may, therefore, not be helpful at all. Simultaneously, let’s say there’s a separate programme to support students with acquiring the language of instruction — where do we send our student? If we sent the student to both programmes, would this require further engagement outside school hours?

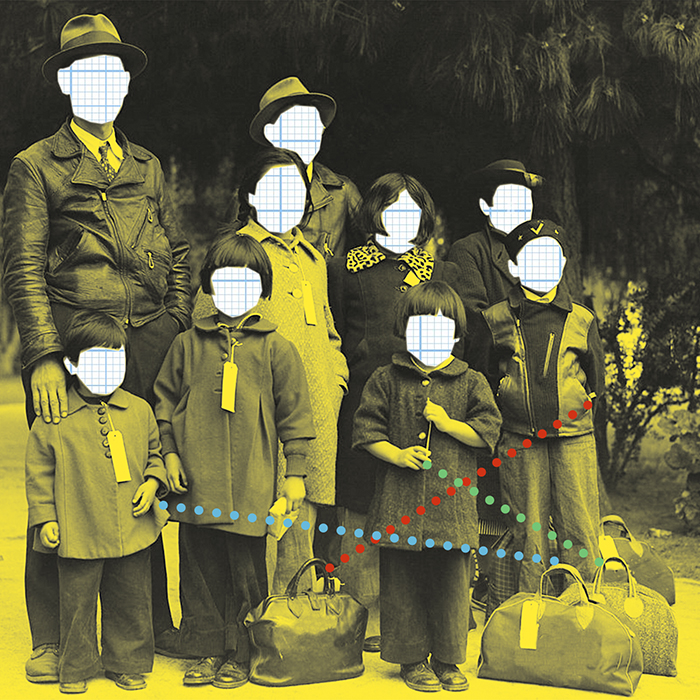

Let’s assume we sent our hypothetical student to both programmes. These placements could put additional scheduling burdens on our student’s parents, who may already be struggling with balancing parenting responsibilities and work responsibilities, and can ill afford to lose a day’s work due to their precarious financial situation. Add to this the social stigma our student will face due to the various identity markers mentioned above (having ADHD, being impacted by poverty, being from a migrant background), and this sets up the student and their family for a less-than-ideal academic experience. Teachers and professionals within the school system should learn to be conscious of this, including being aware of the fact that schools don’t exist in a vacuum. They exist within a cultural and historical context which impacts their everyday functioning.

The BRIGHTER FUTURE project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.